What I have written so far might potentially seem incongruous or over-ambitious. How can a book like this do justice to the scientific material, yet also say something about the social history as well? I lay this out as carefully as possible in the Introduction and set up the project as one of mapping the inner senses and of conducting an archaeology of inner sensations. Not everyone picks up a book and goes straight to the first page. But if you do, in this case, you will see the narrative pattern laid out that starts with a recounting from news footage of a ‘handshake’ at the University of Pittsburgh in 2016 between then-President Obama and Nathan Copeland, a paraplegic research subject in a wheelchair.

The man in the wheelchair had a brain implant connected to a robotic arm, a procedure pioneered at the University’s Rehabilitation and Neural Engineering Laboratory. I had interviewed the lab director and seen footage of Nathan previously, and learned about the process of mapping the cortex. The point about Nathan’s robot arm is that he not only feels touch but also gets the sense of proprioception from it, the felt position of the arm in space. Hence, he could locate as well as feel a ball, or shake the hand of the President of the United States. This is the point of entry for trying to understand how inner senses such as proprioception were first identified and measured.Having read the Introduction, your appetite would be whetted to continue with the first chapter, which launches into the historical search for sensations of movement and proprioception.

From German physiologists trying to investigate what they thought was a distinct Muskelsinn or ‘muscle sense’, and the inability of other physiologists like Sherrington to find such a sense, we end up with the neurosurgery of American-born Wilder Penfield in the Montreal Neurological Institute, who conducts a similarly invasive mapping of sensations across the somatosensory cortex and pioneers open brain surgery in the 1930s.

Penfield famously collaborated with a medical illustrator called Hortense Cantlie to produce an illustration called the sensory-motor homunculus that can be found in almost every introductory textbook in psychology that covers the senses and movement. Actually, these were two related homunculi, the sensory and the motor. These are stylized representations of a little human which indicate where in the brain the different body areas and sensations are located. If point x on the brain surface is stimulated, what is the result? The awake human subject reports tastes, smells, or shows movement for example. Reading the Introduction and Chapter 1 will offer the historical context for some of this very recent work on touch and proprioception through Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCI).

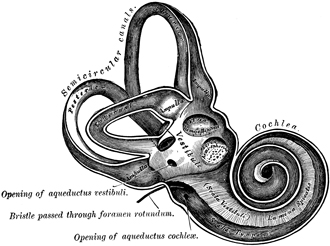

Although there is a long historical arc over the course of the book, each chapter is self-contained, each covering a forgotten or less-encountered interior sense. Fans of archaeology or architectural theory for example might be drawn to Chapter 3 on the ‘oculomotor’, that is, the connection between eye movement and the inner ear.

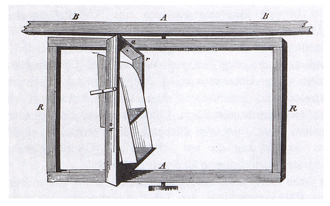

Again, recent scientific studies help pave the way for a deeper historical understanding of bodily orientation and balance, where the pedestrian body and its mode of encounter with buildings and Roman floor mosaics are used as ways into a more embodied appreciation of encounter with the built environment. Thus, I help build a historical-conceptual patchwork for the reader by means of nineteenth and early twentieth century art historians such as Heinrich Wölfflin, and the renowned scientist Ernst Mach, among others.It turns out that, once you start looking into the history of scientific discoveries about these areas, what starts as rather vague and indistinct sensation becomes abstracted and disentangled through observation and measurement through instruments in the laboratory and then later, with more mobile versions of those instruments, out in the field.

That is, on racetracks, in workplaces, and, for Étienne-Jules Marey and his measurement of animal movement, literally ‘in the wild.’ Pursuing this subject matter in this way will have different implications for different readers. For one, it leads to an alternative history of neuroscience. Questions asked in antiquity about ‘inner sensation’ become more fully realized through the rise of a distinct science of physiology in the nineteenth century, as it decoupled from anatomy in the teaching of medicine, and the rise of what Marey called the ‘graphic method.’

Our understanding of the body and its physiology changes as a result of the tracing and representation of these previously indiscernible sensations and processes.For another, in observing and then graphically representing traces of sensation and movement, the unfolding chronology in the book veers very deliberately into the social history of technology and the inexorable rise of workplace observation. The key discoveries between the mid-nineteenth and early twentieth century in this area have implications for labor, industry, and society at large because of industrialization and wartime manufacture.

We end up with the so-called ‘scientific management’ of Frederick Winslow Taylor and the husband and wife team of Lillian and Frank Gilbreth. It is a short leap from the early twentieth century photographic techniques of Edweard Muybridge, Étienne-Jules Marey, and the Gilbreths to the more invasive technologies of workplace surveillance, and the kinds of physiological instruments like Marey’s sphygmograph to the kinds of smartwatches which monitor our pulse every minute of every day on our wrists.