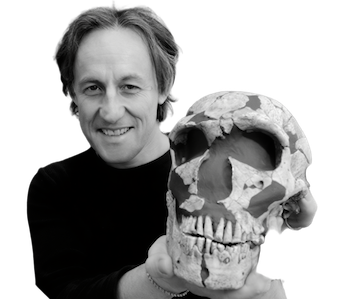

Is this what you would call a golden age of research?It's a combination of things. There has been a huge amount of excavation work and research over the past 150 years, so a lot of material is stored in museums, and often it just sits there. Parallel to this, there has been this explosion in scientific methodologies, techniques, and instrumentation. So in my career as a radio-carbon scientist for example, I’ve seen scientists initially able to analyze things that were large in size: a radiocarbon date of a bone required something like half a femur! Now, however, we can analyze biological remains that are milligrams in size using particle accelerators. We have new mass spectrometers, new ways of doing chemistry, CT scanners for looking inside bodies, LiDAR for mapping sites from the air. It is amazing that we can do all these things that we couldn’t do before, and answer new questions, old questions, and so on. It really is a “Golden Age” in terms of research into the ancient past and the origin of humans.I think that the best example of this is in the field of ancient genetics. When I started working in the Paleolithic field with my colleagues in Oxford, we could get DNA out of animal bones, maybe, but certainly not human bones because they were just too contaminated. We contaminated them just by touching them, such was the ease with which contaminants transfered to surfaces and into bone remains. We also found that microbial and bacterial contamination swamped anything human, even if it could be sequenced reliably. Subsequently, using new chemical methods and new sequencing approaches, it’s become possible to revisit the DNA sequencing of human bones and to sequence genomes from specimens that are thousands and sometimes hundreds of thousands of years old. This research has exploded over the last few years.In fact, in my book I’ve got a really nice picture, which shows the number of genomes that have been extracted since 2010, and it’s going up exponentially. In fact, earlier this year there were three publications in Science that came out which had 700 new genomes from people who lived 20,000 to 30,000 years ago. You couldn’t believe this could happen even a decade ago, and yet here we are. It’s incredible to think too that we now can get DNA out of archaeological sediments. DNA from dirt! The Denisovans were identified based upon the DNA from a tiny finger bone from Denisova Cave in 2010; a new species of human, but even if we didn’t have any of those bones, it is sobering to think that we’d still have evidence for that human group just on the basis of DNA that has been recovered in the last couple of years from sediments in the same cave. It’s almost as though we don’t need actual bones anymore!So it’s exciting to be working in this field currently, because there are so many things we can do and reveal. Ancient DNA has shown us that humans interbred with one another, and so the old models of human evolution, where we saw a fairly unilinear picture of humans evolving into different forms of human have been replaced by a model that is more akin to a braided river, in which humans evolved but occasionally hybridized with one another. This hybridization has been shown to take place in the animal kingdom quite commonly. Different sub-species of baboons in Africa, for example, hybridize frequently with each other on the boundaries of their range, but for some reason we’ve always thought humans were different. We’ve always thought humans don’t do that but the DNA evidence is showing that this is not true, and that humans and Neanderthals and Denisovans, and probably others too, whenever they met they had sex, and they often had offspring. Sometimes those offspring had children themselves, sometimes they appear to have found this difficult presumably due to isolatation, but nonetheless hybridization did occur.What is interesting is that this hybridization brought with it pieces of genetic code that have important implications for us today; sometimes negative, as in the case of Diabetes 2-related genes we inherit from Neanderthals, but sometimes beneficial, as in the gene variant that helps Tibetans to cope with high altitudes and which came via Denisovans. We are just learning more and more about the function of this ancient acquited DNA.