If a potential reader were to pick up my book, I like to believe that were they to turn to a random page, they would immediately be intrigued and drawn in by any of the many diverse cultures and histories I describe. The response I aim for from readers is “Huh. I didn’t know that,” getting them enthused for accompanying me on our adventure through the history of Native America. Being a bit more realistic, I think that I would direct readers first to the Prologue as it sets the tone of the book, preparing the reader for our journey.One thing I try to make clear in the Prologue is that the book is about real people, people who we should credit for marvelous achievements in adaptations, in architecture, in art, in agronomy, and in astronomy. At the same time, a clear-eyed presentation shows that some groups engaged in warfare, some kidnapped people, and some practiced human sacrifice. In other words, the people of Native America shouldn’t be objectified or romanticized by stereotyping them, positively, negatively, or benignly. They aren’t symbols. They were and are people with all that implies for their genius, creativity, and inventiveness.That’s one reason why I highlight in the Prologue the “Crying Indian” ad broadcast on TV as part of an anti-littering campaign in the 1970s. Readers of a certain age will remember endless re-airings of the heart-wrenching ad featuring Iron Eyes Cody (who actually was, as it turns out, Italian) canoeing through a pristine wilderness and coming ashore upon a polluted landscape. There, adding insult to injury, a thoughtless driver throws trash at his feet. The one tear streaming down the Native man's face in the final close-up gave the ad its sardonic name. Though it seems innocuous enough, and appeared to present Native People in a positive light, as the conscience fueling the environmental movement, the ad presented them as powerless. The crying Indian is a ghost from another era. Instead of showing modern Native People actively trying to fight environmental destruction through protest, by voting, or by cleaning up the mess the Native person in the ad cries. Compare this to the genuine story of, for example, the Tunxis in Connecticut who, as I discuss in Chapter 18, were active participants for decades in legal proceedings to recover land taken from them.

They didn’t just grin and bear it. They didn’t cry. They fought it in the courts. The Native People of North America weren’t naive waifs confronting a great civilization; they created their own distinct, unique civilizations who fought their subjugation every inch of the way, sometimes through warfare as shown in Chapter 17 (the Pueblo Revolt and the Battle of the Little Bighorn are good examples). The Prologue sets the stage for the rest of the book, a respectful treatment of a history too often stereotyped, romanticized, objectified, or simply ignored.As I was working on the book, I visited the Institute for American Indian Studies, a wonderful museum and research facility in Washington, Connecticut. While there, I photographed their outdoor exhibit that includes replicas of indigenous structures including a wigwam and a “longhouse.” The latter is more typical of the region to the west of the Hudson River, among the people who call themselves the Haudenosaunee, which, not coincidentally, means "People of the Longhouse.” You probably know them as the Iroquois (Chapter 10). I posted some of those photos on Facebook and received some very nice comments about the beauty and practicality of these structures modeled on Native homes in the Northeast that date to more than 800 years ago.I also received one disparaging comment that, perhaps in my naiveté, actually surprised me.

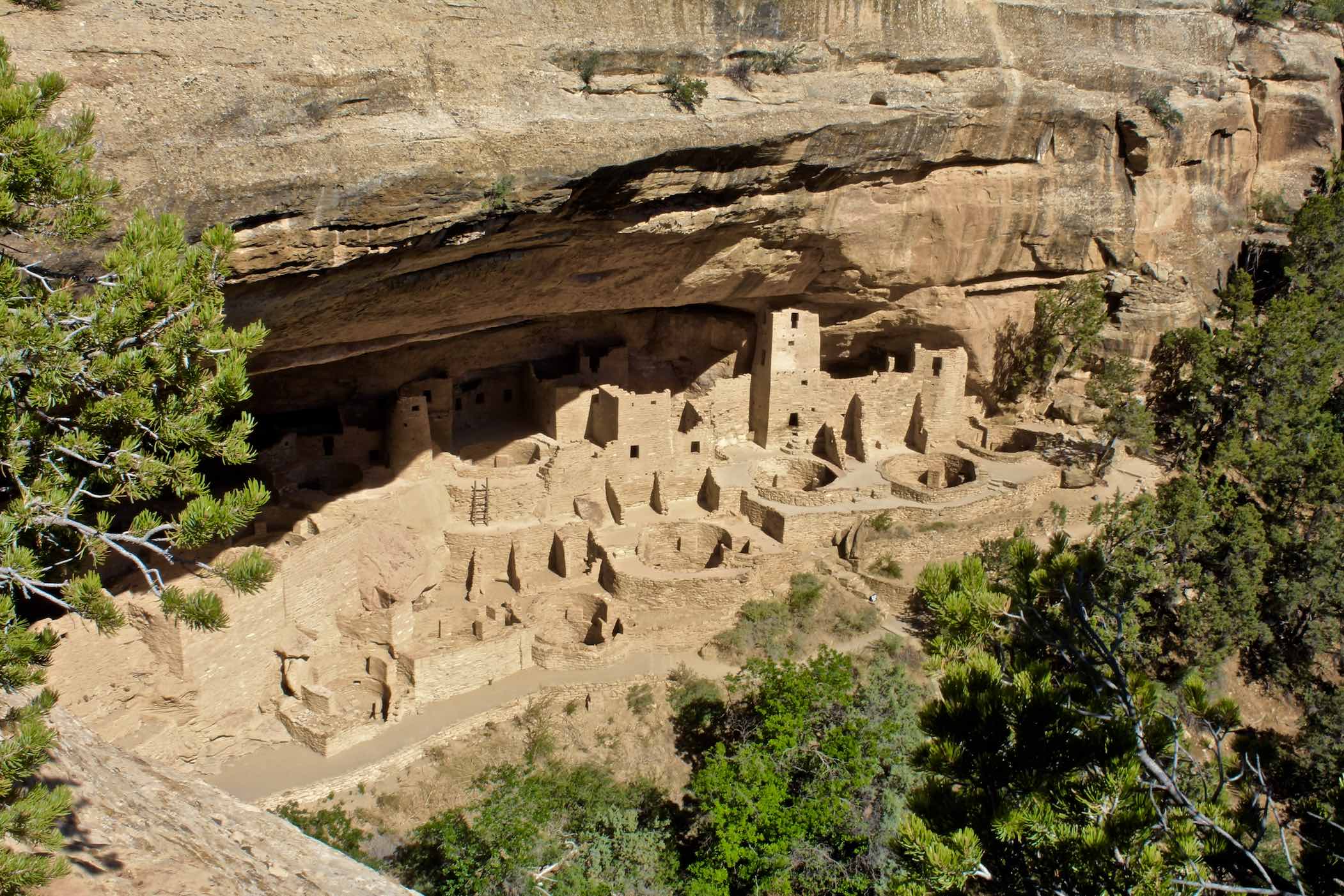

The person derisively pointed out how it was readily apparent from my photos that Indians were primitive and backwards, living in “mud huts” while, during the same period, Europeans were building churches and castles.I found that level of ignorance and bias astonishing, even by the incredibly low standards of social media. Even just technically it was wrong; wigwams and longhouses aren’t “mud huts,” they were ingeniously constructed of bent saplings with thick bark, reeds, or expertly woven mats cladding the structures to render them waterproof. More important though is the fact that these Native structures, both in terms of their beauty and practicality, were more than equal to the houses of ordinary European folk living during the same time period. Further, it might surprise the person who reacted to my photos that most Medieval people weren’t living in castles. In that regard, instead of comparing apples to oranges—Native domiciles to European castles and churches—lets compare the clearly beautiful and impressive Medieval castles to marvelous Native architectural achievements like the multi-story, 800 room, 800-year-old apartment house called Pueblo Bonito in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico (Chapter 14). Or, why not compare an impressive European church from the same period to the cliff dwellings at Mesa Verde, Colorado (Chapter 14). For example, Cliff Palace is ensconced in an alcove in a cliff, has multiple three- and four-story towers, and extends the length of a football field. To say that these Native architectural achievements are unworthy in comparison to European architecture of a similar age is nothing more than nonsensical bias.The level of ignorance and thoughtlessness expressed in the response to my simple Facebook post about wigwams and longhouses should not be ignored and, to be honest, inspired me throughout my Native America book project. The indigenous residents of North America deserve attention and respect and I hope that in joining me in our journey, readers will come away with a new or renewed appreciation for Native America’s First Peoples.