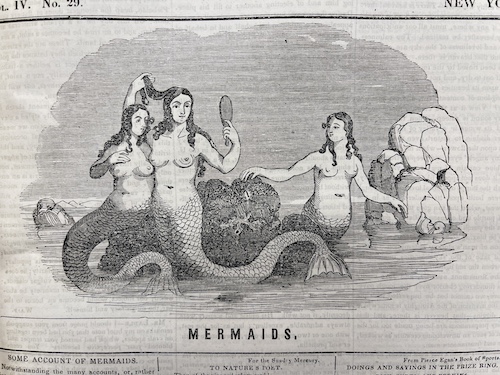

I imagine that a curious reader browsing through the book would first be intrigued by the pictures. Identifying, gathering, and preserving pictures important to the early history of mass visual culture in the US was a key aspect of this project. Although these pictures were produced in very large editions, their materials were ephemeral, and many are now rare. Some no longer exist in their original media but only in disappointing microfilm copies. Some seem to be lost entirely.The book reproduces three wood engravings that P. T. Barnum arranged to have published on the front pages of three different New York newspapers on the same day in 1842 (see pages 78 and 79). All portray mermaids. This was an advertising stunt masquerading as news items. The pictures and accompanying essays were intended to raise the question of the existence of mermaids in conjunction with a new exhibit at Barnum’s museum. He was hosting the so-called Feejee Mermaid, a dried, blackened object made by stitching together nearly invisibly the torso of a monkey and the body of a fish. Barnum urged prospective patrons to view the exhibit themselves so they could decide whether it was real or fake.A portrait of Andrew Jackson, made just two months before his death, was published in the Democratic Review in 1845 (page 168). It looks like a photograph, but it was made before mass printing of photographs was possible. Even more remarkably, it anticipated the look photographic prints would have in a decade or two, when new processes introduced paper prints with distinct forms and a broad tonal range. A talented engraver named Thomas Doney produced the printing plate from a daguerreotype by photographer Edward Anthony (reproduced on page 172).Another noteworthy illustration shows the front page of the first issue of Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing Room Companion, published in 1851 (page 297). Market demand for this illustrated weekly magazine was so great that by the third issue the publishers realized they would need to make adjustments. They regrouped and started over with a new format, larger print run, and more pictures. The illustration on the original front page shows the bustling Quincy Market building at Faneuil Hall in Boston, the hometown of Gleason’s Pictorial. The picture was drawn by a staff writer for the paper. The fact that a writer was pressed into service as an illustrator calls attention to the challenges posed by the shortage of capable artists and wood engravers in the US at the time. I have been able to locate only one surviving copy of this initial issue.

While I was writing this book, the immediate response I would most often get from people when they heard the title was “so it’s about the invention of photography?” There are two problems with this response. First, it attributes the flood of pictures to technological innovation. Rather we should wonder why a particular sort of image technology was sought by inventors at precisely that time. In the case of photography we know that between 1790 and 1840 at least 20 different people were trying to find a means of fixing the image projected by a camera obscura. Second, it assumes that photography was a mass medium from the moment of its invention. On the contrary, photography’s transformation into a viable mass medium was the result of sustained effort over many years. Several other picture technologies—wood engraving, lithography, steel engraving, electrotypes—were immediately capable of producing tens of thousands of copies of an image. These were the technologies that enabled—not caused—the flood to begin. The fact that so many high-volume image technologies appeared in a span of about 50 years is a clear sign of intense historical pressures.This book tries to understand these historical pressures by looking closely at early mass-produced pictures—who was making them and why, what functions they were serving, and what benefits and costs they entailed. The case studies show that mass-produced pictures rapidly assumed many important functions. They supplemented verbal texts—and in some respects overshadowed them—for conveying news and information; portraying people, places, and events; focusing public discourse; selling things; educating and instructing; generating excitement and aesthetic gratification; promoting and disguising political agendas; shaping social identities; and building and undermining social bonds. Pictures were invaluable to wide-ranging communication needs of a new mass society and an expanding capitalist market. As a result of the flood, all sorts of individual and collective experiences were increasingly mediated by visual representations. Modes of perception and cognition were changed by it.A direct line connects this formative moment with our present one. Beginning in the mid-19th century every generation has commented upon the exponential growth in the numbers of pictures circulating in their incessantly modernizing world. The book lists a series of these comments. For example, already in 1860 one magazine noted that “Photography threatens to flood the world with the amateur performances, on paper, of the Sun. Stereoscopic ‘views’ are becoming as thick as autumn leaves, and almost as cheap. Lithographs are everywhere -- even on posters and billheads, and the promise is that ‘the masses’ will not famish from want of something to look at. We may well characterize this era as that of promiscuous production in the way of pictures.” To call the production of pictures “promiscuous” was to say that picturing was being used more often than was necessary. Unmistakable anxiety was mixing with excitement.I hope the book will focus our thinking about pictures, give it a historical framework, and provoke reflection on the extent and strangeness of our present cultural dependence on them.