The book looks to modern and contemporary literature and film from Turkey and Iran. The chapters examine the temporalities of the late Iranian auteur Abbas Kiarostami and the Turkish Nobel Laureate Orhan Pamuk; they interpret other Middle Eastern modernist writers including the poets Forough Farrokhzad and Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar, as well as the Ottoman novelist Ahmet Midhat Efendi.

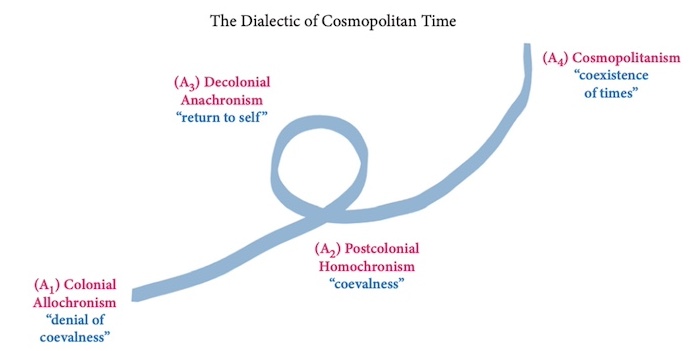

The book also asks how we tell the politics of history, using the Louvre Abu Dhabi as a case study. That chapter addresses a problem that’s emerged in the field of comparative literature: once we add non-European sources to our canons, how do we integrate those languages and cultures into the same world history? Should we, in fact, incorporate European and non-European sources into the same timeline? Or does imposing European timelines (“Eurochronology”) onto non-European subjects do violence to these texts and the histories and calendars that produced them? Do certain eras of world history—such as that of modernity—welcome a single global timeline, given the interconnectedness imposed by colonialism and capitalism? And do earlier eras, such as the medieval era Before European Hegemony that Janet Abu Lughod describes, reject such interconnectedness, instead welcoming a multiplicity of culturally specific timelines? These are the political and historical stakes that the museum poses in Chapter 5.

The book closes with my translation of Ahmet Haşim’s “Muslim Time” (1921). In November 2023, I stumbled upon a snippet of the Turkish text at the Pera Museum in Istanbul. As soon as I saw it, I knew I had to translate it. It perfectly encapsulates the book’s main argument. In it, Haşim describes the intrusion of “alafranga” or European time into Turkey. (He calls it a “siege”!) This alafranga time, synonymous with the 24-hour clock, interrupted the “alaturka” rhythms that previously organized Ottoman life. Those rhythms corresponded to sunrise, sunset, and the five calls to prayer.

The book arrives at a timely moment. Whether it’s the meme that encourages us, however facetiously, to “reject modernity, embrace tradition” or “retvrn” to the past; the debate about the origins of the United States (1619 or 1776?); the anxiety about the future of the climate or world order; or the revanchist global right—the present convenes a war about the meaning of the past, present, and future. Maybe framing these colliding temporalities, and the ideological worldviews they represent, through the concept of cosmopolitan time can help us to better understand, and ultimately, overcome, the impasse in time society finds itself in. That’s my hope.