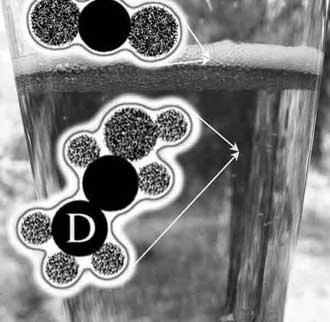

Named after Charles David Keeling, a distinguished carbon-cycle scientist, the carbon atom Dave serves, I hope, as a literary device that aids in revealing the fascinating paths that actual carbon atoms take during their global circuits. Through carbon atom Dave I present the carbon cycle from a carbon atom’s point of view. Each chapter includes a vignette from the life of Dave. These vignettes relate to the substantive technical content that follows. In the first several chapters, for example, Dave’s presence in an alcohol molecule in a glass of beer illustrates how a loop in the global carbon cycle works. His passage through a gas analyzer in the early 1960s leads to the topic of the discovery of the worldwide rise of CO2.

Dave’s transit from the atmosphere into the ocean shows that circuits extend from plants to soils to air to water and back.I was not able to introduce everything I wanted to by following a single atom of carbon. Dave, for example, entered the biosphere naturally—from the dissolution of a crystal in a limestone cliff during the last Ice Age. Some of the pathways in this book had to come from carbon atoms brought into the biosphere by the combustion of fossil fuels. Thus, I bring in several other atoms: Coalleen, Oiliver, Methaniel. By tracing the stories of these atoms, we appraise the magnitudes of various carbon fluxes to and from the atmosphere and the stability (or lack thereof) of the global carbon cycle in the past.With the twin purposes of enhancing the enjoyment of our being alive as carbon-dependent organic beings and preparing the way for the later chapters, I planned the chapters in the first half of the book as relatively short primers on carbon fluxes that circulate among the great carbon-containing “bowls” of the biosphere.

In the later chapters, I unfold the issues that are so challenging with respect to the future. These chapters, too, include episodes from the lives of my named carbon atoms—for instance, Oiliver and Methaniel are released from a burning stick used to cook a school lunch in Rwanda, and Dave passes through a wind turbine. But the material in the later chapters is denser, and the tone more impending as we project CO2 emissions into the future.

The debates about the global environment, warming, fossil fuels, new energy systems, and global equity are coming on strong and I try and bring readers face to face with all these vital topics. I hope that readers will gain an expanded vision into the future. They will start thinking about and visualizing the world situation fifty years ahead. They will become concerned about the future in a way that I truly believe they should be. They will come to see the world system differently, more interconnected, and know how their local actions and lifestyles have global consequences.

A major part of the book’s most significant message, I offer, is its examination of relationships among wealth, energy use, and CO2 emissions. CO2 emissions are tied to the present and most likely near-term trends in the global economy. It is possible to show, therefore, why CO2 will continue to rise and at what rate, given world energy policy, and what the uncertainties are given what we know about the carbon cycle. Slowing the rise will necessitate further development of sources of energy that do not emit CO2, such as carbon sequestration, solar, wind, nuclear, and others, all potential answers to the gamble about whether alternatives could be in place in time.

There are difficult issues that go beyond any debate, say, about a few wind turbines offshore of Cape Cod. What would massive deployment look like for new kinds of energy?I as well as many others believe that in the intensifying debates about the global environment, climate warming, fossil fuels, and new energy systems, we will eventually confront the issue of global equity on a per capita basis. The emissions of CO2 waste spread globally no matter where those emissions originated. So the economic “haves” are giving not only themselves the increased greenhouse effect. They also are giving it to the “have-nots.”

Will the U.S. in the year 2050, for example, still have per person emissions that are hundreds of percent points above the world averages, and thus continue to serve as the supreme example of wealth through CO2 emissions? Will the world even have an example of a complex, economically developed society that has low emissions? The economic machine will probably roll on pretty much like it has been, at least for the global total, as developing countries increase their emissions. After 2050 the gamble that the developed portion of humanity is taking with the state of the world and its capabilities to deploy options becomes much more serious.

But what will the U.S. and other heavy per capita emitters do? Can a new paradigm for economic wealth be set in place by 2050?